“Are we out of the town

yet?”

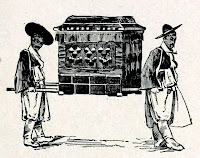

The muffled voice from

inside the enclosed palanquin startled the palanquin bearers. It was sweet and lilting –

that of a young girl in her earliest spring, approaching the cusp of bursting

into blossom.

The two bearers were

brothers. The younger one in front, Dae-Ho, hesitated before finally answering:

“Yes, mistress. We have left your town and are now on the main road to Seosan.”

The two bearers were

brothers. The younger one in front, Dae-Ho, hesitated before finally answering:

“Yes, mistress. We have left your town and are now on the main road to Seosan.”

The older, sterner

brother, Dae-Hyun, who bore the palanquin from the rear, registered his

disapproval in the way he ever-so-slightly altered the cadence of his loping

stride, so that Dae-Ho’s own rhythm was jarred.

The voice spoke again: “Are

there many people on the road? Are there warriors in shining armor marching?

Are there merchants on caravans bearing wondrous cargo? Are there noblemen in silk

robes and tall hats riding on horses?”

Dae-Ho glanced at the old

man they were passing, who was shuffling forward slowly, bent over by the bale

of hay on his back. In the distance, up the dusty road in front of them, were three

or four peasants walking the opposite way, towards them.

Dae-Ho said, “No,

mistress. There are not very many people traveling at this hour.”

“Oh,” the girl said, that

one utterance freighted with disappointment. After a mile or so had passed, she

spoke again, hopefully: “Are we passing groves of cherry trees with pink

flowers? Can you see castle walls with banners waving? Are there snow-capped

mountains in the distance?”

Dae-Ho’s eyes swept

through the rice paddies that quilted the countryside, the farmers’ hovels huddled

at the foot of the modest hills to the south, the spindly trees and brush that lined

the road. “No, mistress. We are in a poor, quiet part of the country.”

From behind, Dae-Hyun’s

gruff voice rumbled, “Dae-Ho, be quiet.” Then, in a softer, subservient tone: “Mistress,

we beg your pardon. My brother is young and impertinent – and should know

better than to address one of his betters with such familiarity.”

A cheerful laugh sounded

from within the palanquin. “Oh, there is nothing to forgive. He was only answering my questions.” Then, in a more somber tone: “It’s just that I’ve

never been outside of my father’s house, much less outside our town. This is

the first time I am traveling anywhere. But I cannot see anything from inside

here and only wished to know what there is in the world outside.”

Dae-Hyun looked at the swaying

tassels of the fringe that lined the palanquin and obscured its air holes. He

had not considered it before, but inside the box, the girl was in darkness, her

legs doubled over and wrapped in the tight binding of the silk gown that

someone of her station wore; she would barely be able to move. Inside, the air

must be hot and stifling. For an instant, Dae-Hyun’s chest constricted, and once

again, the brothers’ rhythm was interrupted with a slight jolt.

The girl continued to

speak: “Once I am brought to the widow Lady Choe’s household, there I will

likely remain for years – perhaps even for the rest of my life.”

A silence fell. Then, to

Dae-Ho’s surprise, his older brother asked a question: “You are to be married into

the Lady Choe’s house, mistress?”

“Perhaps someday. For now,

I am to be her handmaiden and companion, to keep her company in her old age.

She has sons, but she also has many handmaidens for her sons to choose from. I

am sure all of them are prettier than me.” She went on: “She is very rich, you

know. My mother said that her compound covers an entire city block in Seosan. And

there I will stay, for as long as she wills it, just as I have always been

confined in my father’s house.

“My father was once a rich

merchant himself, but he has fallen into difficult times. He has had to sell off his property little by little to keep my family’s station. Most of his land, most

of his warehouses and goods. And now me.”

Dae-Hyun thought back to

when he and Dae-Ho had entered the merchant’s courtyard earlier that morning to

pick up the palanquin. The merchant’s wife was weeping, the merchant himself

was stone-faced. Their servants were shutting the palanquin’s hatch and the

overseer was locking it up with an iron lock. The brothers had not even caught

a glimpse of the girl; she was already inside the palanquin when they arrived.

The overseer, who had hired them for the job of bearing the palanquin, went to

them with instructions, warnings, threats: the brothers were to bring her

to Seosan directly; they were not to stop on the road; they were to protect the

cargo – the girl – with their lives. Any failure on their part would mean flogging

and imprisonment – and eternal dishonor to their families.

Dae-Hyun ventured, “You

must be sad to leave your family.”

She said quietly, “Yes.”

And after a pause: “And afraid of going to live with strangers I have never even

met. What – what if they are cruel?”

Then she said, wistfully: “If

only I could see out. I have never seen anything outside of my father’s house

and garden. All I know of the world comes from the stories I am told and the paintings

on our walls. What wonders must be out there!”

Dae-Hyun scanned the poor

landscape about him. “Well… there are no noblemen or castles presently, but we

are coming to a bridge.” And indeed, they were approaching a small, wooden

bridge that spanned across a small creek.

“Oh, oh!” the girl said

excitedly. “What does it look like? Is it made of marble?”

Dae-Hyun hesitated. It was

Dae-Ho who answered: “No, mistress. It is made of silver and gold. Oh, how it

blinds me!”

They crossed the bridge.

Dae-Hyun hoped that the girl did not know difference between the sound of

footsteps on wood from that of footsteps on metal.

“What else do you see?”

the girl said. “Oh, please be my eyes.”

Dae-Hyun looked up in the

sky. A crow was making its way from one tree to another, cawing as it flew. He said, “An

eagle, mistress, flying high in the air, with wings spread as wide as… well, as

wide as a dragon’s wings.”

“Oh!” the girl said, her

voice filled with delicious fright. “Are we in danger? Will it swoop down and snatch

the palanquin and carry me away?”

Dae-Ho said quickly, to

allay her fears: “Oh, no, mistress. This kind of eagle only eats barley.”

“Oh? I have never heard of

an eagle eating barley.” She sounded confused – and a little disappointed.

After a moment, Dae-Hyun

said, “My younger brother is trying to assuage your fears – or else he is ignorant.

This kind of eagle can carry off cattle, if it can swoop on them unawares. Do

not lie to the mistress, Dae-Ho.”

“But surely it will not

swoop down on us?” The note of excitement and fear had returned to her voice.

Dae-Ho said, “Do not

worry, mistress. Your father’s overseer gave us spears to protect you with. We

will keep the eagle away if it flies near.” After a moment, he added, “Please

excuse my misleading you before. I did not want you to be frightened.”

“Please, I quite

understand. I trust that you will keep me safe. Please tell me: what else do

you see?”

“Umm…” The two brothers

cast about. They saw a rabbit start at their approach and turn and run into its

burrow. Dae-Ho said, “Mistress, you must be quiet now. We are approaching a

cave where it is rumored a dragon sleeps.”

Dae-Hyun whispered, “Even our

spears would be useless against such a beast. Our only hope is to walk softly by.”

The palanquin closed into

itself in silence, a heavy, palpable thing. After the brothers had carried

the palanquin some distance, Dae-Ho said, “We are safely past the cave now,

mistress.”

A loud gasp of relief came

from the palanquin. The palanquin itself seemed to lighten with the release of fear. She said, “Oh, you must be such brave men to court such dangers.”

The two brothers smiled. Dae-Hyun

said, “Oh, not so brave. Everyone faces such things daily.”

“What else is around us?”

After the dangers they had

put her through, the brothers sought to describe to her more pleasant things: an

enormous temple with sweeping roofs far away that thousands of people visited each day; a forest of mulberry trees, their branches heavy with black fruit; a

river laden with boats carrying precious jewels and exotic spices; mountain

peaks that reached almost into the clouds. And as they approached Seosan at midday

and the traffic began to get heavy and noisy, they were able to give her the

noblemen and warriors and merchants she had desired. Once in the city, they conjured

through their words the castles and banners she had asked for.

In time, they came to the

house of the Lady Choe of Seosan. The large wooden gates opened and they were admitted

into the courtyard, where they were finally able to lay down the palanquin and

stretch their sore arms and legs. The lady herself came out and stood on the

porch entrance, accompanied by servants and her steward, who had the duplicate key to the palanquin’s lock. Dae-Ho and Dae-Hyun glanced at each other, then frantically

looked around the courtyard. They saw a stack of bamboo off to the side by the

wall. They went to the stack and each grabbed a pole. The steward looked at

them in surprise, as if he thought they had gone mad, then went to the

palanquin and proceeded to unlock it.

Servants swung open the

latch and helped the girl out. She was a tiny thing; she could not have been

more than twelve or thirteen. She swayed as she stood up and hung on to the

servants for support. Even as she blinked in the sunlight, she looked not at

the lady, who was smiling down at her from the porch, but around the courtyard,

as if she was searching for something.

Despite their fatigue, Dae-Hyun

and Dae-Ho straightened their backs and stood up their bamboo poles alongside

their bodies – like flagpoles, like spears. The girl saw them standing at

attention as if they were soldiers and smiled. Then the servants closed in

around her and brought her up the steps to the lady, and they all went inside

the house, leaving the steward to show the brothers out the gate.

(May 2013)